The original System Shock came out during a time when artificial intelligence was simply a sci-fi trope in a blockbuster movie. Now, as it creeps steadily into every corner of our lives, we’re using it to drive cars, write emails, and create audio deep-fakes of Barack Obama playing Five Nights at Freddy’s with Donald Trump. As we reevaluate our usage of modern technology, perhaps it's time to revisit some of the games that put us on the path to progress. Nightdive Studios’ 2023 remake of System Shock reminds us just how far games have come in an almost 30-year gap between the two releases — and where our expectations for games now lie.

Like the original, the game takes place in the year 2072. A drone camera sweeps through the retro-futuristic cityscape of New Atlanta, with architecture plucked straight out of Blade Runner. A news announcer speaks of mega corporation TriOptimum and its earth-orbiting Citadel Station entering its tenth year of operations, specializing in robotics, genetics and pharmacological research. Three subjects indicative of a plot that’s about to take a nasty turn.

Shortly after, the drone hones in on our protagonist: a nameless hacker who, after attempting to access restricted neural implants from TriOptimum’s server, is captured by a security team and brought before a TriOptimum executive, Edward Diego. In exchange for removing the ethical restraints of Citadel Station’s AI, SHODAN, the hacker is promised the neural implants complete with the surgery to install them. After removing the restraints from SHODAN, the hacker is put to sleep, only to wake up deep in Citadel Station now overrun by mutants, cyborgs and aggressive robots under SHODAN’s control.

The game wastes no time getting into the thick of it. With the exposition succinctly established, players now need to move through the station's many levels and prevent SHODAN from extending her destructive reach to Earth. The beats are effectively the same as the original. Where System Shock’s overhaul really becomes apparent is in its visual updates. The flat panels covering the corridors now feel more intricate, accentuated even further by the vibrant lighting. The game isn’t afraid to fill its environments with color and cashes in hard on the retro, neon aesthetic. A closer inspection reveals just how stylized System Shock is, with environments given a semi-low resolution appearance, reminding you that it’s still a retro game at heart.

There’s an immediate contrast between the dazzling, polychromatic visuals that decorate the walls of Citadel Station and the sheer bluntness of violence that has been enacted. Remains of crew members, decimated and dissected by SHODAN’s controlled forces, are littered throughout the levels and always remind you just how alone you are this far out into space.

The contrast is effective, visually, but the same can’t be said of System Shock’s overall tone. In the few interactions our protagonist has with other characters, he shows flippancy. Not verbally, our hacker doesn’t speak, but a few crude gestures gets the point across. There are occasions where SHODAN speaks with a GLaDOS-like insincerity. When you progress from one level to the next, you’ll hear charming elevator music as if the whole experience is just a jolly jaunt through space. But between it all lies some pretty harrowing tales, mostly of the crew’s futile attempts of surviving SHODAN’s brutality; final moments captured on audio tapes, or scenes of unfortunate personnel undergoing transformations into mindless cyborgs. Both of these angles are fine and can co-exist within a game, but System Shock never quite bridges that gap. The two tones instead feel very separate, and jarring.

Sadly, a confused mood isn’t the primary issue for System Shock. Rather, combat is a player’s biggest hurdle. The first weapon you’ll pick up is a pipe to be used as a melee weapon. There aren’t many of these to find throughout the game, and with good reason. They’re slow and problematic to use against everything except the basic mutants. The second you find a gun, you’ll likely never look at a melee weapon again unless you’ve really messed up. Most importantly, they’re just not very fun to use. Melee weapons are supposed to have a bit of weight behind them so that you feel it when you connect against an enemy. Here, adversaries barely stumble when hit and it never feels very satisfying or impactful. There’s no block or evade mechanic, either, so it’s hard to come out of a close encounter unscathed. Once you start running into enemies that have their own projectile attacks, bullets or other, it becomes nearly impossible to close the distance enough to get some swings in. With such a short shelf-life of usage, it makes you wonder why melee is even an option at all.

Combat with guns doesn’t fare much better. They’re more useful and certainly have more stopping power than the pipe or wrench, but they also don’t execute very satisfying attacks. Enemies will hardly react to being shot at, making you wonder if you’re doing any damage at all. The most enjoyable to use are the Frag Grenades which can effectively turn a room full of mutants or cyborgs into a Jackson Pollock, leaving you to collect any dropped valuables from among the viscera. Ultimately, it results in combat that rarely feels tense, with interesting enemy designs wasted on bland encounters. Locutus of Borg comes striding towards you down a confined, dramatically-lit corridor but an easy shot or two sees him crumple like a tin man.

One glance at System Shock, both the remake and original, invites comparisons to early Doom games — level design, environments, even the perspective. But the similarities are surface level. The gameplay is vastly different. We talked about System Shock’s combat feeling uninspired, something we wouldn’t necessarily tolerate from Doom, but it’s almost forgivable thanks to where the game does excel. Complementary to its puzzles, which exist in more forms than just routing power through circuit boards to open doors, System Shock is not as linear as it first appears. There are a few objectives for players to complete within the game that aren’t immediately obvious. If a player pays enough attention to the data logs they collect, they’ll realize there’s more to do than simply climbing the station’s levels to reach SHODAN. The more you put into System Shock, the more you’ll get out of it. There’s a lot to uncover, but don’t expect anyone to hold your hand and lead you to it. Players are given near-full independence to reach and decipher the game’s complete ending.

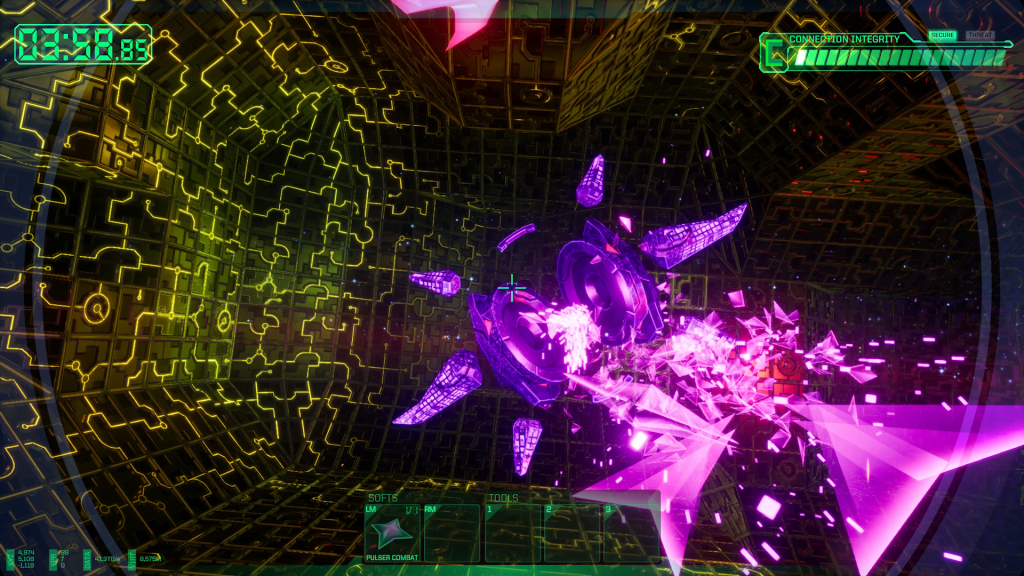

The trek through Citadel Station is periodically broken up by delves into Cyberspace, a space combat-style minigame with wireframe-like environments. Personally, I’ve never been much of a fan; my urges to replay Kingdom Hearts are quickly squashed when I’m reminded of the Gummi Ship segments. Despite this, the stark improvements made to Cyberspace here are undeniable. Aside from the overall vibrancy and graphical boost of the remade minigame, it’s much easier to navigate and offers more intuitive controls. The runs are a little bare-bones — you can usually succeed by spamming the shoot button. Completing the run will unlock a key route or interaction somewhere in the level, so you can continue on towards the horrors that await you.

Healing items are a hot commodity. You’ll need to horde dermal healing patches and first-aid kits, both of which are in short supply. There is, however, an abundance of food and drink items to be found across Citadel Station: candy bars, sodas, chips. They’ll be on shelves, tables or in the pockets of the recently deceased primed for looting. Looking at their inventory description reveals they can be used to restore health, except they can’t. They don’t serve a purpose at all. You can’t consume them, they won’t drop into your consumables hotbar — they just take up inventory space. You can’t even sell them, as they won’t return any Credits. They’re just junk items that lead you to believe they have status benefits. Granted, these types of items appeared in the original, but they served no purpose then, either. You could argue that they exist to make the world feel more lived in; crew members probably would have food and empty wrappers in their pockets. But this isn’t a hyper-realistic RPG, this is an action title with puzzle tendencies. If I cannot use an item, in any capacity, then it doesn’t need to be there.

No ads, our video library,

No ads, our video library,